Early Records of Baroon – pre settlement of Maleny and Montville

Long before the now well-known hinterland town names such as Maleny, Montville and Mapleton there was Boorum (Baroon). Records of its significance can be found in early reports of white settlement.

The Simpson Report – May 1842

The first reference to Baroon is from Dr Stephen Simpson’s report to the Colonial Secretary on May 30 1842 following an interview with Bracewell and Davis who were rescued runaways who had spent time with local tribes). The Blackall Range holds deep significance for the many tribal groups that visited the area; in particular, ‘Boorum’, an open space in the middle of “the great Bunya Scrub, where the natives hold their great meetings” This is the local tribe’s name for their ‘meeting place / fighting ground’ on Obi Obi Creek where Bonyi Bonyi were celebrated. These festivals saw as many as 600-700 Aboriginal people gather every three years when the fruiting Bunya trees provided ample food for the several months tribal members gathered to exchange stories, settle tribal disputes, perform corroboree and feast. Alternatively the word ‘boorum’ may be associated with either ‘rat kangaroo’ or with the word ‘burun’, the edible tops of the cabbage tree palm which were described as plentiful by a young Tom Petrie. Whatever its derivation, ‘boorum’ has been Europeanised to become our current Baroon Pocket and Baroon Dam.

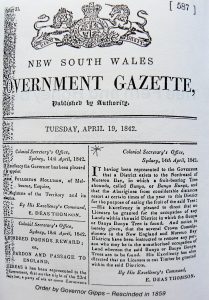

Government Gazette – April 1842

Bunya Proclamation 1842

Earlier, in March 1842, paving the way for the expansion of free settlement in Moreton Bay, the Governor of NSW, Sir George Gipp visited the Gossner Mission at Zion Hill (Nundah, Brisbane) to encourage the brothers to establish a mission 80 – 90 miles to the interior where ‘a type of tree (bunga-bunga) grows with much good fruit that tastes like sweet almonds but is much larger, a favourite of the blacks.’ (Pastor Schmidt).Then on the 14th April 1842, the Governor decreed the Bunya Proclamation which disallowed the felling of any Bunya trees, or any settlement or timber licences to be granted where bunyas were found. Effectively, no colonists could claim this portion of land, and yet he had offered it to the German missionaries just a month earlier.

Despite the Governor’s hopes to establish a mission near where the aboriginal people gathered, and despite being ‘enchanted with Baroon, a valley of 300-400 acres of mostly fertile land, free of trees or with fine timber, deep pools, permanent water, the whole place circled by high hills with innumerable Bunga tree, the missionaries could not bring wagons into the site and were shown an alternative area, well timbered with good soil and a lagoon near what is now Commissioner’s Flats. (Frank Woolston)

Ludwig Leichhardt’s Journal – 1843

Ludwig Leichhardt, the explorer and naturalist recorded his travel from Durundur to Baroon in 1843 with John Archer along with Waterstone and three aborigines who carried provisions as the land was too steep for horses. He described Baroon as ‘a creek fed by shady gulleys, of the brushes passed it; low ranges, all covered with thick brush, all of igneous formation surround it, many a bunya tree looks down on the capers of the sable children of the forest and brush’. Leichhardt’s poetic description confirms the abundance of the bunyas on the slopes down to the Obi Obi and in a letter dated 9th January, 1844, to Lt Robert Lynd, Barrack Master, Sydney, NSW he writes,”there is a a little valley, an open plain, in the midst of these brushes which cover perhaps, an extent of 50 miles long and 10 miles broad, This plain, they call Booroon and it seems the rendezvous for fights between the hostile tribes who come from near and far to enjoy the harvest of the Bunya. I went to Booroon. A creek fed by the shady gullies of the brushes, passes it.”

Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of early Queensland dating from 1837

In 1845, Tom Petrie, then 14, attended the Baroon Bunya Festival (Bonyi Bonyi) at Baroon Pocket. Tom arrived in Brisbane in 1837 when his father, Andrew Petrie, was appointed Engineer of Works at the small Penal Settlement of about ten buildings. From early childhood, Tom spent time with the Aborigines around Brisbane and learned their language fluently. He spoke Undumbi, a dialect of the Gubbi Gubbi or Kabi Kabi language group.

Tom travelled from Brisbane to Baroon with a group of 100 Aborigines. In the afternoon of the fourth day of their journey the party camped at the creek near Mooloolah. According to historian F.P. Woolston, the Aborigines and Petrie came up from Mooloolah along one of the ridges which rise up and ends under the crest of the Range. They then went down the track, which is now an extension of Mill Hill Road.

The Aborigines would gather in Baroon when they first arrived at the Blackall Range. Petrie saw between 600 and 700 Aborigines at Baroon. He is the only person to record the Bunya Festival in detail.

The Bunya Proclamation of 1842 did not attempt to define land boundaries and as a consequence, created an intentional but unadministered Aboriginal reserve just as land elsewhere was being taken up for farming. Following Queensland’s separation from New South Wales in 1859, the Bunya Proclamation was repealed in 1860 to enable the passing of the Unoccupied Crown Lands Occupation Act 1860. The dispossession of Aboriginal people in this area began in earnest. Land squatting, selection and timber licences were soon issued for the land that had once been sacred to the Aboriginal people.

An 1880s gathering at Bridge Creek which joins the Obi Obi at Baroon Pocket

With the interruption and prevention of traditional use of these natural resources the Aboriginal population soon dwindled. Deaths from introduced diseases, shootings, poisonings, conflicts with settlers and starvation from not being allowed to hunt and gather traditional food all took their toll. Traditions and lifestyles, which had remained unchanged for many thousands of years before European settlement, were altered forever.

Under a Queensland Act of Parliament (1897) and subsequent legislation, most of those who survived were forcibly moved to missions such as Barambah (renamed Cherbourg), Yarrabah (near Cairns), Palm Island (near Townsville) and Deebing Creek (near Ipswich). Here they were confined and used as labourers and domestic servants. http://www.mary-cairncross.com.au/traditional-owners-sunshine-coast.php

Amendments to the Act, removing restrictions came too late because by then the local tribes had been decimated.

Few Aboriginal descendants have returned to the Blackall Range. However, those that have, proudly uphold their cultural traditions and acknowledge the traditional role of the Bonyi Bonyi at Baroon with contemporary celebrations of Bunya Dreaming.

References:

Woolston, Frank. (1983) ‘Early European Visitors to Baroon Pocket’ unpublished article written for Montville Historical Group

Woolston, Frank. (1989) ‘Early European Visitors to Baroon Pocket’ in The Range News pps 20-21

Maleny and District Centenary Committee. (1978). By Obi Obi Waters : stories and photographs of early settlement in the Maleny district, Blackall Range, south eastern Queensland. Maleny, Q : Maleny and District Centenary Committee

Petrie, Tom & Petrie, Constance Campbell, 1873-1926 (2013). Tom Petrie’s reminiscences of early Queensland : (dating from 1837) (Queensland classic edition). Salisbury, Brisbane Watson Ferguson & Company

Photos:

Bunya Proclamation 1842: Kelly, P. (1988) Tree Fern and Honey Bee, Mapleton Centenary Committee

1880s Gathering: Stan Tutt. (1986) Sunshine Coast Heritage, Vol 1, p.81, Melbourne, Craftsman Publishing

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.