Sawdust and Steam: The story of the Flaxton sawmill, 1936 to 1963 by Gordon Plowman is a delightful account of the history of the sawmill along with entertaining anecdotes of the many folk his family encountered while living in Flaxton. This 9000 word story has been divided into 7 parts for ease of reading online.

Part 1 (The Case Mill, 1936)

Part 2 (The Hardwood Mill, 1938)

Now read on for Part 3

Also working in the Flaxton forest were three sleeper cutters who also had to comply with forestry regulations and pay royalties on the trees they harvested. The best trees were allocated to the sawmill for processing into sawn timber. Dud trees, often hollow, could be used to make railway sleepers and the sleeper cutters used these. They paid less in royalty for trees of lesser quality.

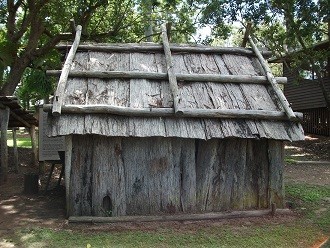

As railway lines extended along the length and breadth of Queensland, sleepers of suitable durability and complying with strict railway standards, kept thousands of sleeper cutters in employment. At Flaxton, Bill Cotterell lived in a bark hut, even the roof was bark, across the road from the sawmill and unlike others of his trade, he worked alone. He cut down trees with axe and cross-cut saw, split billets to size with axe and wedges then expertly dressed each sleeper using his broad-axe. Bill took great pride in producing sleepers of excellent quality and finish.

Bark Hut Gympie Woodworks Museum

Hewing out railway sleepers wasn’t his only skill. He built a bush lathe modelled on those used hundreds of years ago and during the peak of the English arts and crafts movement. It consisted of a rope attached to a foot pedal at one end and a springy sapling at the other. By passing the rope around the piece of wood he wished to turn, he could take a cut with his chisel each time he depressed the foot pedal. This simple machine took patience and skill to operate but Bill managed to produce beautiful wooden bowls, vases, containers and even walking sticks. He gave most of his creations away after he had applied finishes which he made himself from Condy’s crystals, copper sulphate and a variety of extracts from bush plants and berries. On one occasion when the Flaxton cricket team could afford to buy only one bat, he cut a large branch from a fig tree and carved it into a perfectly balanced replica of the genuine willow, but all in one piece. That bat blasted balls in cricket season after cricket season, a testament to the skills of this talented bushman.

Bill Cotterell made a name for himself in the wood-chop arena. Aged 60, he still competed in wood-chop events and the Courier Mail once described him as, “The grandfather of Queensland axemen.” After a lifetime of work in the bush Bill retired to Coolum.

Two more sleeper cutters worked from a rough-built shack further along Mill Road past the sawmill. Jack Toomey and Charlie Brooker slaved away in their lonely bush environment for several years.

A Mapleton man, Ted Richards, called regularly to load their sleepers on his truck and take them to the railway depot. In a terrible accident, Ted was backing his tractor in the bush near Mapleton when the seat support broke. He fell backwards and the tractor ran over him and killed him.

When the Flaxton mill started production in 1936, it was by no means the first one in the district. Pugh’s Almanac mentions C.J.Wyer’s mill in operation as far back as 1900. Dad found what remained of a pit-sawyer’s operation near the western end of Mill Road which almost certainly pre-dated Wyer’s mill. We found relics of two other sawmills, one located approximately at the junction of Mill Road and Alice Dixon Drive, and the other at the far end of Old Mill Lane. Neither Alice Dixon Drive nor Old Mill Lane existed then. The original road in to the latter took a completely different route to the north-west. Relics at this site showed evidence of a boiler explosion. A rusting relic of the boiler showed how it had blown apart along the longitudinal seam. Messrs Collis and Schlinker are also known to have operated sawmills in Flaxton.

The Flaxton sawmill supplied orders for sawn timber from far and wide but their mainstay customer in the earliest years was Chapman and Carter, a firm of Brisbane builders stationed at Kedron. Most of the mill’s output went by truck down the winding road between Montville and Palmwoods where it was loaded on to railway wagons for the journey to Brisbane.

The sawmill used several varieties of trees, mainly blackbutt, but orders for heavy bridge timbers with cross sections measuring, for example, 10 inches by 6 inches (254 x152mm), they usually used brush box (Lophostemon confertus), which attracted a lower royalty payment.

Fifty years or more before Flaxton mill commenced operation, bullock teams hauled loads of red cedar (Toona ciliata), from the forests. When valuable cedar and beech ran out, they turned their attention to hardwoods and pine. The old tracks carved out by bullock wagons served as pathways along which logs were delivered to Flaxton mill. An old bullock driver, Charley Chambers, bought some of the earliest supplies of logs in by snigging (dragging) them in with his bullocks. Then, Mick and Keith Oaks used their tractor to snig logs in from the forest. Later still, Eric and Reg Jones brought in logs on their GM 6×6 trucks. These were the years just before the chain saw revolutionised the timber industry and displaced thousands of forest workers. A sharp axe, a cross-cut saw, steel wedges and a springboard were, at that time, the stock-in-trade of the tree fellers.

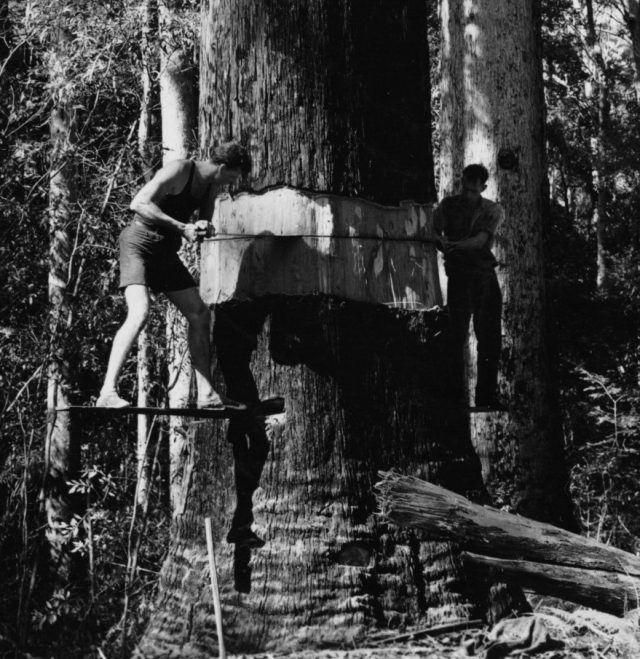

An axeman preparing to fall a forest giant firstly inspected it to decide in which direction it should fall. He then set to work with his axe and chopped a ‘belly’ deep into the wood at the butt of the tree in the direction he wanted it to fall. Moving to a position opposite the ‘belly,’ two men manned the cross-cut saw and sawed through the remainder of the butt wood. Often the saw jammed and heavy steel wedges belted in behind the saw relieved the pressure.

After expending enormous amounts of energy, huge quantities of sweat and usually a few choice words, the tree which had spent perhaps 100 years or more growing up toward the sky, creaked and groaned its last protest before it came crashing to earth. Now lying horizontality on the ground, the log was divested of unwanted limbs, cut to length with cross-cut saw and the bark removed. A crawler tractor came clanking through bush and scrub to snig the log to a stockpile beside the track, ready for loading on to a truck.

Large forest trees are often hollow at the base and this part is useless for milling. In this case, the tree fellers must cut through the tree above the hollow. They do this by working at height from a narrow platform called a springboard.

Cross-cut sawyers working from springboards. (National Library of Australia)

Skilled axemen cut a small groove into the tree trunk and insert the toe end of their springboard. A metal shoe on the end grips into the wood and the axeman can now climb on to the springboard and commence chopping. If he needs to go higher, he cuts another groove higher up and inserts another springboard. This process is repeated until he reaches working height where he chops out the ‘belly.’ Two men now reposition their springboards so they can use the cross-cut saw to cut in behind the ‘belly.’ As soon as the tree begins to fall, the sawyers grab at the butt to steady themselves as the tree shudders and shakes and thumps into the ground. Springboard grooves can still be seen in some of the old tree stumps in Flaxton Forest.

To have watched experienced axemen precariously balanced and working at height on their springboards is an amazing and unforgettable sight. Today’s health and safety’s people would doubtless fall into a pink fit if they could see the way we used to do things.

The three original owners of the mill continued with it until just before the outbreak of WW2. In 1939 they sold the mill to Hamilton Sawmills, one of the many companies owned by M.R. Hornibrook’s construction company. The sale, in retrospect, may have been fortuitous.

Sawmillers always faced stiff competition for contracts within the building and construction industries. In changeable and uncertain times of war, only those with a large customer base or rock-solid contracts were assured of a continued income. Hornibrook’s growing construction company satisfied both conditions.

The story of Sawdust and Steam continues with Part 4 (1939, New Owners)

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.