Sawdust and Steam (Part 5, War Years in Flaxton, 1940)

Sawdust and Steam: The story of the Flaxton sawmill, 1936 to 1963 by Gordon Plowman is a delightful account of the history of the sawmill along with entertaining anecdotes of the many folk his family encountered while living in Flaxton. This 9000 word story has been divided into 7 parts for ease of reading online.

Part 1 (The Case Mill, 1936)

Part 2 (The Hardwood Mill, 1938)

Part 3 (Other Timber Cutters, 1936-39)

Part 4 (New Owners,1939)

After Dad sold his share in the Flaxton mill, he bought a mixed farm, better described as a subsistence farm. Fortunately, he did not have to rely on farm income alone. Hornibrook kept him on at the mill as manager, engine driver and general factotum. He held a steam engine driver’s certificate and sometimes worked at Mapleton and Conondale mills when they were an engine driver down.

The farm, only half a kilometre from the mill, was originally owned by a well-known identity of Flaxton, Montville and Caloundra, Emily Bulcock. Emily Bulcock, nee Palmer, began her working life as a school teacher and she has the distinction of serving as the pioneer teacher at Razorback school, now known as Montville. She married Robert Bulcock, a Cleveland orchardist, and the couple later moved to Caloundra. The Bulcocks owned property in Caloundra and Bulcock Street and Bulcock Beach are named after this family.

Emily achieved fame as a writer, journalist and poet. Her brother, Vance Palmer became a successful writer and radio broadcaster. Some of his works appeared in the school curricula and he wrote a series of newspaper articles, “Tramping the Blackalls.”

One of Emily’s poems appeared on the front page of the ‘Redland Times,’ and in 1922, the Sydney Bulletin, in celebrating Anzac Day, devoted a full-page to one of her poems, appropriately illustrated by Norman Lindsay. Her prolific writing career included the publication of three books of poetry. Emily was appointed Order of the British Empire in 1964 for her contributions to literature.

Our family happily made the transition from the weatherboard cottage beside the sawmill to the bigger farm house. For mother, who had lived within the confines of the forest for the previous five years, it must have felt like walking into a new sunshiny day. Now she could look out over cleared paddocks and green hills and see two neighbours’ houses in the distance. Some of the feeling of isolation evaporated.

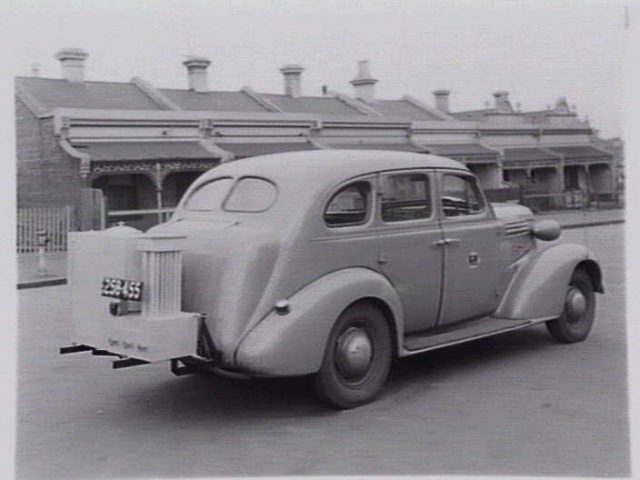

Dad now had a longer walk to the sawmill but everyone was used to walking particularly since wartime petrol rationing drastically reduced the availability of fuel. Petrol rationing drove motorists and taxi drivers and some truck owners to install gas-producers on their vehicles. These devices burnt charcoal as a substitute fuel and although this reduced the horsepower, it did keep more vehicles on the road including one belonging to Hamilton Sawmills manager, Albert Porter. His big black car now had bulky gas producing equipment bolted to the rear. Charcoal, which burned in a specially designed canister, produced poisonous carbon monoxide gas, the fuel substitute used in place of petrol.

A presentation of Engineers Victoria had this to say about vehicular gas-producers:

“We are interested in the production of carbon Monoxide. It is combustible (and explosive), odourless, colourless highly poisonous – indeed it is nasty stuff and very dangerous. That we ever had a government encouraging its widespread use and a population somewhat eager to embrace the habit of making the stuff in the back of the car and indeed carting the whole “factory” around with them, is a sign of the moment.”

Car fitted with gas producer (State Library of Victoria)

Unfortunately, there were no other known petrol substitutes and the use of producer gas became widespread. This presented another problem, charcoal was in short supply and in some locations, impossible to procure.

Dad’s friend, Trevor Carter, owned a carrying business and when petrol rationing became law, he fitted gas-producers to some of his trucks. He had trouble finding a reliable charcoal supplier so Dad came to his rescue. With the help of explosives and pick and shovel he dug an enormous pit in the ground fifty or so metres away from the sawmill. He stacked sawmill waste and dead tree branches from the forest into the pit. He set the wood in the pit on fire than quickly covered the open top with old sheets of corrugated roofing iron. He shovelled dirt around the edges and over the iron sheets to reduce the amount of oxygen reaching the fire.

Charcoal is formed by burning wood in an oxygen deficient environment. Dad’s charcoal burning fire smouldered for days. When it cooled sufficiently, he opened the pit to reveal a pile of charcoal, ready to fuel Trevor Carter’s trucks. After WW2 with petrol again freely available, Dad filled in the charcoal pit. Right up to the 1970’s, subsidence could still be seen where the charcoal pit once was.

The uncertain years of WW2 after the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbour, occupied Singapore and bombed Darwin, Broome Townsville and three other northern towns, Australians in general and Queenslanders in particular feared an invasion from the north. The nation had neither the weaponry or military might to repel an attack by the Japanese Imperial Forces. Desperate times demand desperate solutions. The military command and the Queensland government decided on two controversial policies designed to save lives and to frustrate the advance of an invading enemy.

It seems almost unimaginable these days that the first of these, a scorched earth policy, could even be considered. Let the ‘Melbourne Herald’ of February, 1942, tell the story:

“Scorched Earth in Queensland.”

“All state departments have planned a scorched earth policy if necessity arises in Queensland. Primarily, responsibility for deciding which areas shall be scorched will rest with the Northern Command. Arrangements have been made by the Department for the destruction of foodstuffs and works in vulnerable areas, and the evacuation or destruction of cattle. Dumps of emergency foodstuffs were being laid down throughout the State,”

The second emergency and last-ditch policy the Government thought might be necessary involved the mass evacuation of all citizens in the path of Japanese invading forces. Our tight-knit rural community in Flaxton wasted no time in planning their evacuation should it become necessary. The Nambour Chronicle of June 1942 details these arrangements:

“Evacuation”

“Public meeting at Flaxton school discussed arrangements for evacuation if it became necessary. Details of every household in the district had been determined and it was found that the seating in available motor vehicles was sufficient to accommodate everyone. Outside help was not necessary should the need arise to evacuate every resident of the district.”

This newspaper excerpt typifies a time when most Australians did whatever needed doing without depending on government assistance.

Part 6 (The Mill and the Army, 1942) continues the story of Sawdust and Steam by Gordon Plowman

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.