researched and written by Gordon Plowman (2021)

The pillars either side of the Montville Memorial Gate pay tribute to the fallen and those who served during the Great War, and recognise those who were rejected for military service. (To mark the centenary of erecting the Memorial Gate the sandstone pillars were restored, 2021)

Over 60,000 Australians from a population of just under five million, paid the supreme sacrifice during World War One. The remains of those who were killed or who died while serving overseas were not brought back to Australia. Their loved ones were deprived of the opportunity to conduct a funeral or to say a last good-bye. A pall of grief swept the country and a deep desire to recognise the debt paid by both the fallen and those who survived became paramount.

War memorials erected as a tangible token of respect and remembrance may, it was thought, offer some solace to the grieving families and provide shrines where others could mourn or express their appreciation for those who heeded the call to arms.

War memorials took many forms such as memorial buildings, avenues of trees, a cenotaph, an obelisk or the most common, the statue of a soldier with rifle reversed and head bowed. The Montville community decided to build a beautiful memorial gate to adorn the front entrance to the School of Arts building.

In the fresh mountain air, residents of the small farming community of Montville brimmed with excitement. Today would be the day when all their past efforts of planning and fund raising would come to fruition. The organisers of this auspicious event were up early to add the finishing touches. The community had worked for more than two years toward this moment and everything had to go to plan. This was Armistice Day, 11 November 1921. On this day, for the first time, the Memorial Gate was in readiness to be officially presented for all to see.

The scheme to build the memorial gate began as an idea at a meeting back in 1919. The Montville community, justifiably proud of all those from the district who had, without hesitation, enlisted to fight in the most horrific war the world had ever experienced, now wished to build a memorial to them. Residents willingly contributed ideas, money and promised their own labour in an effort to build a monument worthy of those who had sacrificed so much and those who had paid with their own lives. After much discussion, a decision at a meeting on 30 October 1919 got the project underway. The Brisbane Courier reported on the outcome:

“Montville: A meeting of residents was held in the School of Arts to further consider the soldier’s memorial scheme. A motion was passed agreeing to the scheme for erecting memorial gates. The following committee was appointed to carry out the project: Messrs Harvey, Swain, W.J. Butt, T.H. Brown, Mesdames F.W. Thompson, N. Isaacs and W. Skene.

The subscription list was handed round, and the additions made brought the total promised to £70.”

Just over one week later, the Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser reported that at a meeting of the Commemoration Committee, a number of collectors were appointed for the Soldier’s Memorial fund, so that a start can be made on the erection of the memorial gates.

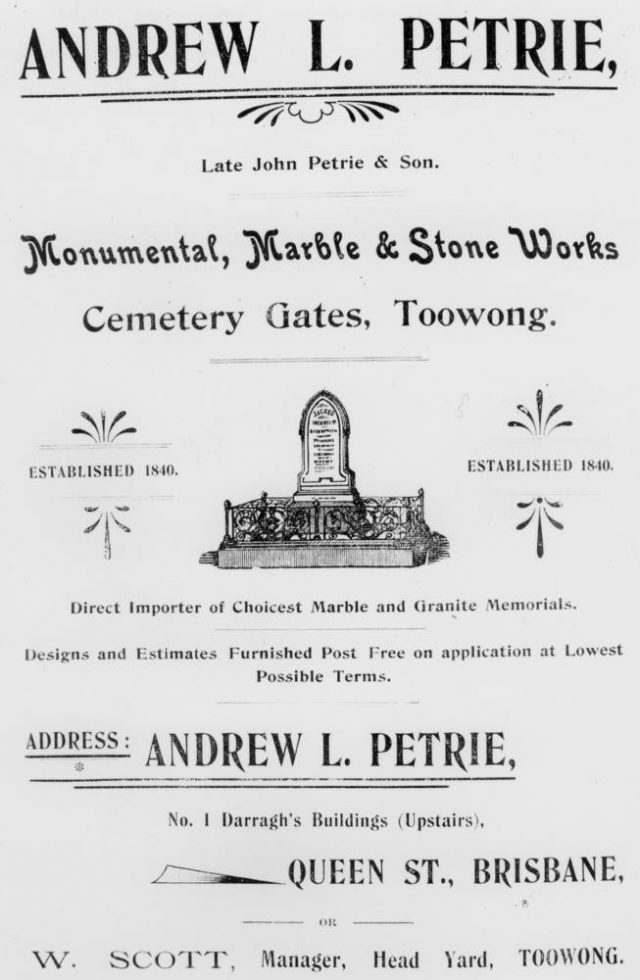

Brisbane monumental masons, Andrew L. Petrie and Son, were selected to carry out the contract. The gate would comprise four pillars built from Helidon sandstone. The two front pillars, each 7feet 6 inches (2.3 metres), high and situated each side of a wrought iron swing gate, would each carry a white marble tablet suitably inscribed with the information supplied by the Montville committee. A dwarf curved stone wall connecting each of the front pillars to its corresponding side pillar was to be topped by a wrought iron palisade. Each pillar would be further enhanced with moulded caps and pyramidal finials. The well-regarded Mr. W. Scott of Andrew L. Petrie and Son would oversee all this work and his superb craftsmanship remains in place to this day, much as it was in 1921.

The arrival of Petrie’s men on 27 September 1921, aroused much excitement. They had come to begin work on the memorial, to lay the foundations and erect the stone pillars. The hope was that the stonemasons would complete their work in time for the official opening planned for Armistice Day on 11 November, less than two months away.

These records come from the A.L. Petrie Papers, Fryer Memorial Library Brisbane :

Letterbook, 29 Sept 1921 Mr Petrie’s Account to the Montville Patriotic Committee: For supplying and erecting two stone pillars with marble panels in face, total height 7½ feet, with 4 feet entrance gates, 2 stone pillars, 6 feet high at sides £116/-/- Plus 15% 17/8 Cutting and Lead inscription, 415 letters at 7d each

Petrie’s men did finish in good time and on the morning of the 11 November 1921, the Montville community came together to witness the unveiling of the memorial gate, to remember those who served in the Great War and acknowledge those who paid the supreme sacrifice.

Advertisement, Andrew L. Petrie, Monumental, Marble and Stone Works

The small crowd assembled near the memorial gate began to swell as farmers and residents from outlying districts came to join in. Schoolchildren who were included in the proceedings excitedly assembled in their allocated area. Then, the official party arrived.

A large Union Jack covered the gate and its supporting pillars. The crowd waited patiently and anxiously for all to be revealed. The plan was for Mr. F. H. Walker, MLA, the local member of parliament to perform the ceremony but when he failed to show, Mr. W. H. Harvey, chairman of the Maroochy Shire took on that responsibility. The Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser recorded the event:

“The knot loosened, the flag was hauled to the top of the adjoining flag staff. The school children were assembled in front and sang, “God Save the King.”

At last, the memorial for which the Montville community had worked so hard was, in all its glory, now on public display. After the ceremony a fete, a concert and a dance provided entertainment for the attendees and raised the much-needed funds to pay the money still owing for the memorial.

Hall and Memorial Gate early 1920s including the picket fence

Those who were at the unveiling on that day saw, for the first time, the completed memorial. The names of The Fallen, well known in the Montville district, brought tears to those many eyes. But the tears were tinged with joy because the thirty-nine names of those who served their country in times of its greatest need, would be forever preserved in stone.

Inscriptions, Montville Memorial Gate pillars

The left pillar is inscribed:

ERECTED BY THE RESIDENTS OF MONTVILLE DISTRICT. IN APPRECIATION OF THOSE RESIDENTS WHO ENLISTED IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-1919.

FALLEN: 6 Names

The right pillar is inscribed:

ENLISTMENTS: 33 Names

REJECTS: 6 Names

The Queensland War Memorial Register has this to say:

“The right roll lists 33 individuals who enlisted and unique to this memorial, there are six individuals listed who were rejected for war service.”

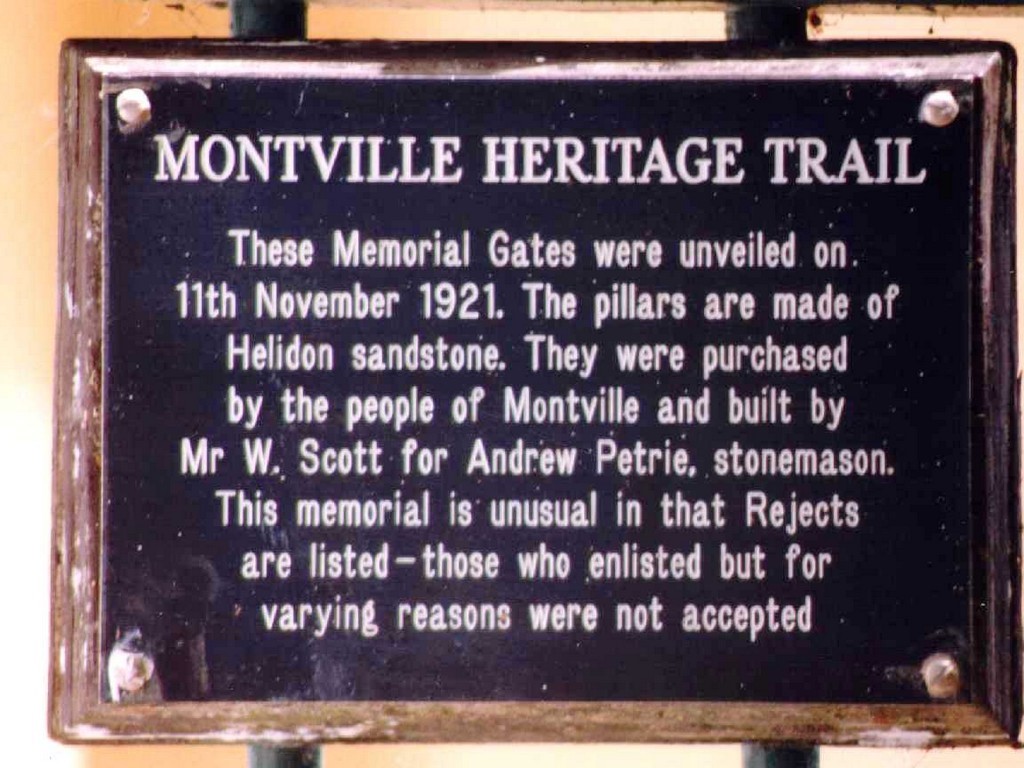

At the right of the Gate is an interpretive plaque providing more details.

Interpretive plaque, Montville Memorial Gate

Many who come to admire the memorial or to pay homage, puzzle over two aspects of the inscriptions; the inclusion of the names of six men who attempted to enlist for military service but were rejected, and the dates given for The Great War, 1914 to 1919. While many memorials date the war years 1914-1918, others, including Montville, prefer the dates 1914-1919, the reason for which is discussed later. But firstly, the story of the rejects:

Toward the bottom of the right pillar, beneath the thirty-three names of those who enlisted, and under the heading, “Rejects,” are six names.

Although the names of rejected volunteers sometimes appear on honour rolls, they are seldom if ever included on public memorials. In this aspect, the memorial gates at Montville are unique. So, why are these names there at all?

Only six weeks after the declaration of war with Germany in 1914, military establishments all over Australia began recruiting volunteers to fight for God, King and Country.

The call to arms arouses patriotic fervour and thousands of Australians from cities and towns, from the bush and from the outback, rallied to the call. By train, on horseback and on foot they came, all eager to enlist in the armed forces and every one of them up for adventure in a foreign land and a chance to show their worth on the fields of battle. Not in their wildest dreams could they have imagined the suffering, the horror or the depravation on the killing fields of the Dardanelles, or France or Belgium.

Thousands rushed to enlist at the beginning of WWI

At first, only the fittest men in the best of health were accepted, the creme de la creme. The plan was to engage men with previous military experience or training with the rest of the force made up by physically fit volunteers between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five years. They were to be at least five feet six inches tall (approx. 1.7 metres), and satisfy the requirement for chest expansion, eyesight, dental health and have no previous injury likely to affect their performance.

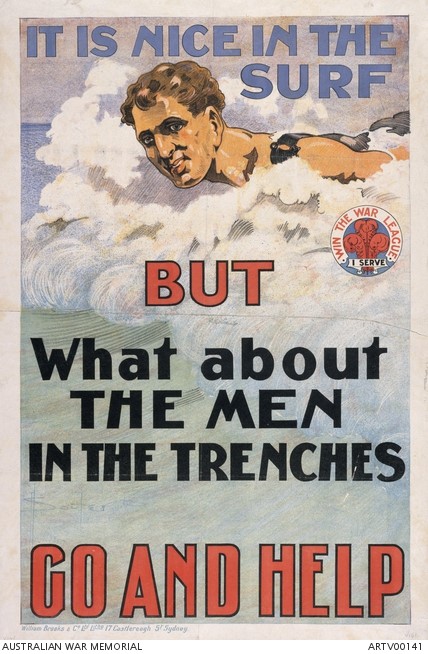

Enlistment poster, WWI

Considering such demanding standards, it is hardly surprising that high numbers of eager young men met with rejection. Throughout the duration of WW1, those men who, in good faith attempted to sign up for military service but were refused, became known as the ‘rejected volunteers,’ or, ‘volunteer rejects.’

As the war dragged on year after year, and thousands of Australians were killed in battle, the enlistment standards were lowered in order to attract enough volunteers to supply fresh reinforcements. Even with the lowering of entry requirements, the reject rate remained high. In a well-documented case in Charters Towers, the medical officer refused enlistment for anyone with defects or deformities, old fractures, hernia, breathing difficulties, heart conditions, poor dentition or poor eyesight. He is said to have rejected a member of the local pigeon shooting club for poor eyesight!

Despite the high reject rate, General Howse, on 30 March 1917 wrote this to General Featherston:

“I am trying to arrange transport for two or three thousand “B” class men; they are absolutely unfit for service. Many of them do not disclose any organic disease upon a carefully conducted clinical examination, but are in and out of hospital, and are quite useless for front line, and practically useless for Home Service…. Far better no reinforcements be sent from Australia as they do no duty, and only cause congestion in our hospitals and Command Depots. The class of reinforcements you are sending are not up to the old standard. Headquarters AIF report that 20 per cent are unfit for the front line.”

The General’s comments notwithstanding, the outstanding bravery and fighting ability of the soldiers of the AIF would soon be recognised as second to none. Under the command of such men as Brigadiers Elliott and Glasgow at Villers Bretonneux and the brilliant leadership of General Monash, the Australians were instrumental in turning the tide of warfare against the determined German Invasion which would eventually lead to the signing of the armistice.

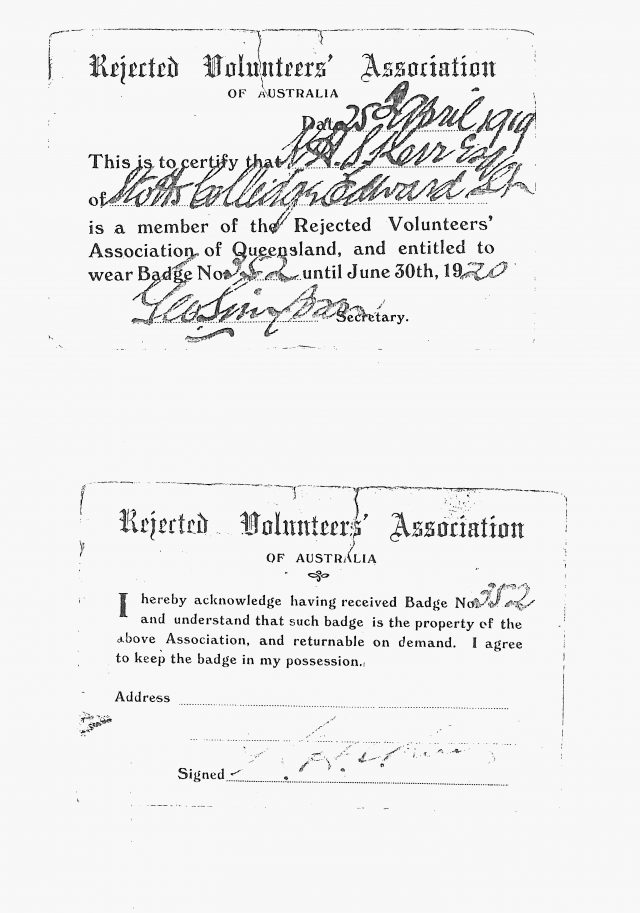

Back in Australia, those who were rejected for military service formed themselves into rejected volunteer associations. Most of these men wore rejected volunteer’s badges to show they had made a genuine attempt (often more than one attempt), to enlist. This, for several reasons, was important to distinguish them from those who did not volunteer.

During the war years, 1914-1919 and for a considerable time beyond, feelings against eligible men who did not volunteer for military service ran high. They were looked upon by many as cowards or conscientious objectors who shirked their responsibility and their duty to their country. When married men with families were accepted for service overseas and eligible young single men stayed safely at home, community anger often ran at fever pitch. Young men who had not volunteered were likely to be given a white feather as a symbol of their cowardice. This created a stigma, not only for the person concerned but for the entire family. This is why the rejected volunteers were adamant in their quest to distinguish themselves from those who refused to volunteer.

Queensland Rejected Volunteer’s badge, WWI

The decision to include the rejected volunteer’s names on the Montville memorial would have been influenced by the prevailing attitudes of that time.

In most instances, the rejected volunteer’s badge or membership of a rejected volunteer’s association was sufficient to distinguish genuine volunteers from non-volunteers. The Montville memorial leaves the community in no doubt.

Rejected volunteer’s membership card, Queensland

At the time of writing, October 2021, details of only a few ‘volunteer rejects,’ had been digitised by the National Archives of Australia where the hard copy records are kept. The reasons why the Montville volunteers were rejected can only be ascertained by doing a physical search of the Melbourne archives and so the reasons for their rejections remains unknown at this time. Unlike WW2 where the Manpower organisation could compel a person to remain in an essential job rather than to enlist, no such body existed at the time of the First World War and the overwhelming majority of rejections were made on medical grounds.

Interestingly, the records at the National Archives of Australia have the Montville volunteer, Joseph Vining, listed under, ‘Volunteer Rejects.’ His story, in a nutshell, is that even with a wife and two children, he volunteered to join the AIF in 1918 and was accepted for military service. A couple of months later while undergoing military training at Enoggera, he experienced severe pain in his foot from a pre-existing injury. Unable to continue training, he was discharged from service on medical grounds. The Montville war memorial, probably quite rightly, lists him under, ‘Enlistments,’ rather than as a reject.

Now consider the dates used for WWI. Most are given as 1914-1918, while a fair proportion of others inscribe the years as, 1914-1919. The War Memorial Trust has this to say:

“1914-1918 are the most common dates for the First World war found on war memorials obviously commemorating the year the war commenced and the year the armistice was declared, on 11th November 1918. However, it is not unusual to find the dates 1914-1919 on First World War memorials. The 1919 date refers to the year when the Treaty of Versailles was signed. This was the peace treaty drawn up by the nations who attended the Paris Peace Conference and officially ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers when it was signed on 28th June 1919.”

Signing of the treaty of peace at Versailles, 28 June 1919

The reluctant signing of the Treaty of Versailles by the Germans in 1919 undoubtedly influenced the dating on war memorials. But there are other reasons which could have swayed opinion toward using the year, 1919.

At armistice on 11 November 1918, approximately 95,000 Australian soldiers were still in France, 6,000 were in hospitals or working in the United Kingdom and 30,000 still serving in other theatres of war. The job of bringing all these men back to Australia presented a huge problem. Some of those in France had to stay at their billets until arrangements were made to bring them to the Australian barracks on Salisbury Plain in England. Many of these men would not embark for their two months long sea journey back to Australia until as late as the second half of 1919. As far as the enlisted men were concerned, their tour of duty wasn’t over until sometime in 1919.

Another legitimate reason for using the 1919 date stems from the British involvement in Russia in 1918-1920. The situation in Russia became confused and complex when Britain and France decided they could intervene in the Russian Civil War, align themselves with the pro-monarchist faction, known as the ‘whites,’ and defeat the Bolshevists, known as ‘reds.’ In August 1918 the British attacked and occupied the Russian city of Archangel.

Britain never officially declared war on the Bolshevist forces and after heavy fighting, they decided to withdraw. About 120 Australians who had been discharged from the AIF to serve as volunteers in the British army, distinguished themselves by their valiant fighting efforts in the North Russia Relief Force in 1919. Two Aussies, Arthur Sullivan and Samuel Pearse were awarded the Victoria Cross. Pearse, unfortunately, died in battle and his award was posthumous.

Samuel Pearse, VC, MM

Australian soldiers were still involved in warfare in 1919 and this presents another factor in favour of using this year to denote the end of The Great War.

For over 100 years, those who have gathered at this Montville shrine to commemorate Anzac and Armistice, mourn the bleak war years but they also rejoice in the triumph of peace. The names written in stone may not be familiar now, but each and every one of them have a story to tell; some are known, many are not. With the passing of the years, we continue to remember those who laid down their lives, those whose war experiences marred them both physically and mentally for life, and those who kept the home fires burning. At this memorial and at thousands of others across our land Australia, we gather together and in so doing, we will remember them.

In Flanders Fields

In Flanders fields where poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

John McCrae.

*****

FURTHER READING:

“Remembering Montville’s Fallen.”

Montville History Group

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

IMAGES:

Montville Memorial Gate Cate Patterson

Andrew Petrie advertisement Public Domain

Dedication plaque Qld. War Memorial Register

Enlistments, WW1 Anzac Portal

Recruitment poster Australian War Memorial

Rejected volunteer’s badge State Library of Queensland

Rejected volunteer’s membership card State Library of Queensland

Signing the peace treaty at Versailles, 28 June, 1919. A.W.M.

Flanders Poppies Pixaby, free download.

REFERENCES:

“In Flanders Fields” John McCrae

Qld. Heritage Register Montville Memorial Precinct

Australian War Memorial Research Centre

National Archives of Australia

Queensland State Archives

State library of Queensland

NEWSPAPERS:

Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser 30 Sep. 1921 and 18 Nov. 1921

Brisbane Courier 23 Oct. 1919

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.