Clive was born on 28 November 1921 in the central west of Queensland, at the Taroom Aboriginal Settlement, a government operated reserve established in 1911. His mother, Amy Blair worked on nearby Hornet Bank Station and Clive’s early years and earliest memories are of growing up in the station owner’s home, sitting on the lowest front step with a cat in his lap. Hornet Bank was owned by the Scott brothers and Clive played freely with the younger children of the household. Mr. Scott was fond of Clive and being an acclaimed horseman bought Clive a horse and taught him to ride.

At this time there was a policy to remove ‘half-caste’ children from their aboriginal mothers and children were institutionalised, or fostered into white families, because contemporary belief held that their white ‘blood’ fitted them for a life better than that available with their Aboriginal family. Although the Bush Children’s Health Scheme wasn’t formally established until 1935 there must have been some similar set up in the 1920s because Clive was taken away with other children to Emu Park for several weeks and on his return to Hornet Bank Station his mother was no longer there. No explanation was given.

It must have suited the Scott family to keep Clive at Hornet Bank Station, but these circumstances changed when he was nine years old. Clive was sent to the Salvation Army Boys’ Home, Indooroopilly, Brisbane between 1931 and 1935 (aged 10 to 14) where he received an education, but for Clive it was a terrible place and he never elaborated. A friend from these years later visited him and recalled how as a little feller Clive used to coach him every night to memorise a piece of scripture in order to avoid the harsh punishment that would otherwise follow.

The effects of separation from his mother, institutionalism, the abuse and denigration and the dissociation from his indigenous community were never talked about but nevertheless impacted on the man Clive was to become. At the end of the war with the help of the army Clive found his mother in Brisbane. It was a sad and difficult reunion for Clive.

Clive came to Flaxton as a teenager and, by 1940, was working on Norman Mayne’s farm which was situated just off the eastern end of Ensbey Road. Norman Mayne grew oranges and pineapples and, in common with quite a few private citizens of the time, he built and maintained his own tennis court. So, it is not surprising to find Clive Blair’s name listed as a participant in tennis fixtures in Palmwoods and Montville throughout the 1940’s, except, of course, for the period of his military service during WW2.

With the outbreak of WW2 and the possible Japanese invasion of Australia, Clive did not hesitate to enlist in the Australian army. At that time, Ensbey Road, then unnamed, was considered to belong to the Mapleton district and his enlistment details record this as his home district.

Farmers, Wal Potts and David McHaffie, both WW1 Veterans, arranged a send-off for Clive to be held in their packing shed. We can only imagine that bygone era with the packing shed at night, standing alone in a grassy paddock with light from the Tilley pressure lamps squeezing out between the cracks around the door. What a wonderful feeling it must have been for young Clive Blair to come inside from darkness into the light with the lingering smell of pineapples and packing cases in the air and the faces of his Flaxton friends all gathered there to wish him well. Perhaps the memory of that evening may have been of comfort to him during his army service far away from home.

Clive was assigned to the 42nd. Infantry battalion and after undertaking a period of training in Queensland, was dispatched to New Guinea. The men of this battalion were thrust into some of the heaviest fighting against the Japanese enemy under extremely difficult jungle conditions. At this crucial time of the New Guinea campaign with the Australians desperately fighting to hold off the enemy, Clive performed an act of extreme gallantry. Lone-handed, he personally attacked a Japanese stronghold, an action that allowed his troops to advance. Let one of the many newspaper reports tell the story:

Under the heading: “7 Queenslanders Win Decoration,” is a brief description of Clive’s gallantry:

“Corporal Blair’s company commander having been killed, Blair collected his men in the vicinity and pushed on to the attack.

Later, when the platoon’s advance was held up by machine gun fire, he outflanked the enemy position, silenced it, and returned to lead his men on.

While endeavouring to silence a further machine gun he was wounded but continued to lead and only withdrew when his injury would not allow him to carry on.”

Clive’s Distinguished Conduct Medal, was the only one awarded to the men of the 42nd battalion.

The Nambour Chronicle of June 1943 acknowledges Clive’s gallantry award and goes on: “We regret however, in the fighting in which Corporal Blair gained his distinction, he had the misfortune to be severely wounded and has been and still is confined to a military hospital.”

On 4 January, 1944, Clive obtained his discharge from military service and made his way back to Flaxton, where, on 10 December at the Flaxton school, he was given a heart-felt welcome home. No doubt the Flaxton community were proud of their Clive Blair, D.C.M.

The Montville and Flaxton District Patriotic Committee, not to be outdone, also held a welcome home function at the Montville School of Arts Hall.

During his stay in military hospital, his therapy included a variety of craft projects. He made woollen rugs and several different kinds of colourful woollen place mats and doilies. He gave some of these to my mother and they adorned the various houses in which we lived for many years afterwards.

On his return to Flaxton after his discharge from military service, he again went to work for his previous employer, Norman Mayne. He also drove trucks for the local carrier, Gordon Mayne who is Norman Mayne’s brother.

One afternoon when I was seven or eight years old, I called in as usual to collect our mail from our collection point just inside J. C. Dixon’s gate. As I walked out, I found a wad of one and five-pound notes. I took it home and handed it to my mother who immediately cranked up the old telephone to make enquiries. It had fallen from Clive’s pocket as he did his deliveries and he was, I am told, exceedingly happy to get his money back. About a week later I arrived home from school and mother said there was a present for me. Now this was unusual. We only ever saw presents at Christmas and on birthdays. Clive had bought me a box of chocolates as a reward for finding his lost money. That was in 1947 or 1948 but I have never forgotten that kindness.

Despite his war wounds and the necessity to attend repatriation hospital in Brisbane periodically, Clive continued to lead an active life. In 1948 he captained the Montville cricket team. David Plowman, a member of Clive’s eleven, remembers the camaraderie of those fantastic weekends when they did battle with bat and ball.

In 1950, my father sold his Flaxton property and bought a sawmill near Emerald in central Queensland. Clive worked at this mill for a time. He and my eldest brother, David, went on a long walk through the bush, looking for trees suitable for processing in the sawmill. Late in the afternoon they headed for home and became lost. Night fell making it impossible to go further so they spent an uncomfortable night lost in the bush. Early next morning in the light of day they immediately recognised their surroundings. They were only a few hundred metres from the sawmill and everyone breathed a sigh of relief when the two hungry bushmen marched into the kitchen looking for a good feed.

Plowman and Sons sawmill was situated on Fork Lagoons Station, 35 kilometres from Emerald along a poorly maintained dirt road. One afternoon, Clive Blair and Harold Plowman loaded the International truck and jinker with a large load of sawn timber. They left at daylight the next morning and drove their load slowly but surely to the railway goods yard in town. They loaded the timber piece by piece on to the railway wagon then filled in the necessary paper work. By this time, they were famished so they walked across the main street to enjoy breakfast at the cafe run by Tony and George Comino. In those days, you didn’t get a great choice of menu; breakfast was what you were given and that was that.

Clive and Harold ordered but when their meals seemed to be taking an extraordinarily long time, Clive called George Comino over. “George,” he said, “We have waited ages for breakfast. Any chance you can hurry it up?”

George said, “The bacon, the sausages and the tomato are all cooked but the eggs aren’t ready.”

Clive said, “We need to get going so just eliminate the eggs.”

George said, “That’s just the bloomin’ trouble. That blessed Tony has broken the eliminator.”

Clive could coax quite a reasonable tune from his harmonica which, whilst stuck out in the bush at Emerald with little else to do other than work or read magazines, he often played. My most enduring memory of Clive is not his harmonica playing but his occasional bursts into song. Sometimes he would sing a well-known song but would almost invariably add his own words. I particularly remember a song, “I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now,” to which he had added his own words. I think he was careful not to sing anything bawdy when I was within earshot.

Moving back to Flaxton, Clive took an active part in the community. If a tennis tournament was scheduled for the Flaxton school court, Clive would arrive there the day before to roll and mark the court and attach the net, all ready for play. When help was needed at a working bee or to erect the annual Christmas tree, Clive would be there. At the Flaxton school reunion in 1996, several ex-pupils, expressed their fond memories of Clive and in particular, his prowess as a ping-pong player.

Clive enjoyed the social dances held at the local halls and it was here he met and courted Elsie Dixon, a young girl with the most astonishing sky-blue eyes and beautiful long blonde hair which she usually wore in a bun.

They married in October 1950 at Chermside, Brisbane and when my father and two older brothers went to visit them in the early 1950’s, he was managing a pineapple farm at Brookfield, near Brisbane and later at Kallangur. Roslyn was born in the Nambour Hospital in 1951 and late in 1954 the family moved up to Flaxton where Clive and Elsie ran Percy A. Dixon’s dairy farm as share farmers. Their son, Andrew was born at this time and the family took up residence at ‘Chermside’, one of the Dixon family homes. The children attended the Flaxton State School, built on the land donated by their great grandfather, Joseph Chapman Dixon an early Flaxton pioneer.

Clive had applied for a soldier resettlement and was successful in obtaining acreage on the eastern slope of the escarpment about 1km north of Montville towards Flaxton. After Elsie’s parents sold their farm in 1963, Elsie and Clive who had also been share farmers with them, putting in many years of work for the farm, needed a new source of income. They had always been part of their community and this continued at Montville. In 1960, Clive took part in a working bee to install lining in the back room of St. Mary’s Hall. He donated the timber which came from the old Kanaka barracks, originally built by J. C. Dixon Snr., on his Flaxton property. Clive acted as the caretaker of St. Mary’s Hall from 1967 until 1974.

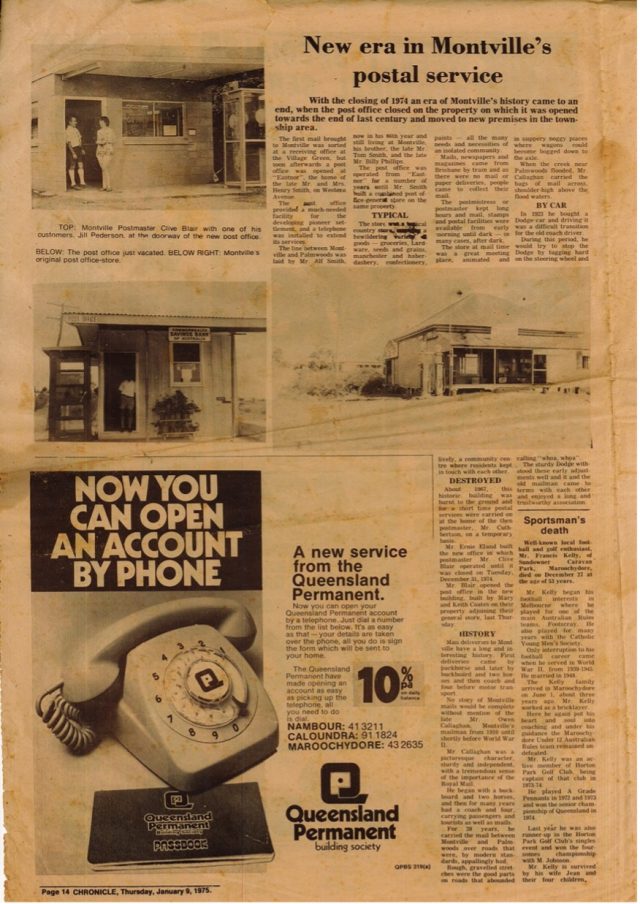

Clive was a good friend of Bob Cuthbertson, the then Montville postmaster, enjoying a game of chess, smoking and reminiscing about their war years. When the Cuthbertson family had to leave Montville, Clive took on the job of Postmaster. That was at the beginning of 1966 and marked a new chapter for Montville’s post office. The original post office and store built around 1912 had been burnt to the ground six months earlier, a severe blow to the community. Bob Cuthbertson had run the post office from his home about three kilometres along Western Avenue until the new post office was built on the same site.

Clive was an attentive and sympathetic postmaster who enjoyed his job and, although PMG regulations had become very restrictive in what it allowed in the post office, Clive always overcame the problem. When there were restrictions about public notices, Clive set up a sandwich board outside the post office to inform the community about local dances, working bees, items for sale, help wanted etc.

The mail came from Palmwoods, and Clive sorted it for collection. The post office was also an agency for the Commonwealth bank. In his eighteen years as Postmaster he heard many an astonishing story when the locals stopped by for their mail, to do their banking, have a yarn, or sometimes just for a bit of gardening advice. Clive grew beautiful hippeastrums and there was often a vase on display on the post office desk.

Clive ran the post office at the old site until it closed at the end of 1974. He then opened the new post office down the Main Street of Montville in January, 1975 beside the general store which had been built back in 1966 to replace the one lost in the fire. Clive saw a lot of changes in the community in his time as postmaster. He was a friend to all and much-loved by the people of Montville and on the last day of work in August 1983, Clive arrived to find the post office festooned with balloons and a huge sign wishing him a “Happy Retirement”. He was both surprised and delighted by this sign of the community’s affection and respect.

Clive enjoyed his retirement, playing in RSL bowls competitions for the Queensland teams Annual Round. Clive was a hard worker, a loving husband and father, a generous friend, a dedicated and much respected community member who should never have been targeted by police because of his Aboriginal heritage, who should never have had to claim he was Greek to explain his dark skin. Clive rose above the setbacks society imposed to be uniquely himself and to accept himself.

Clive’s father was from Scotland and he and Elsie went there to look up his father’s family. Reportedly, they were warmly welcomed and had a wonderful time whilst there.

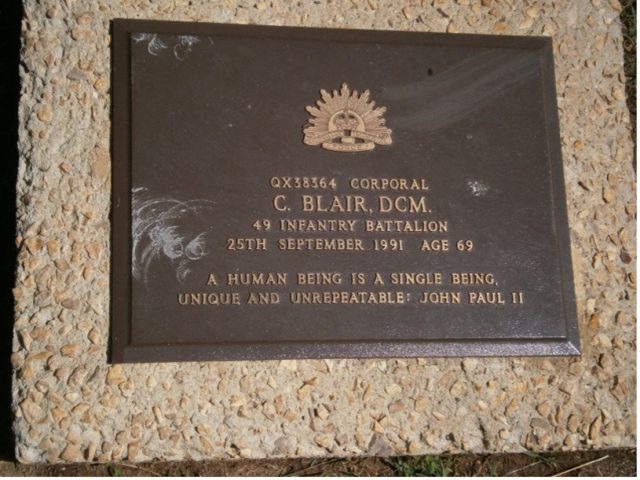

Clive died in 1991 aged 69 years and is buried at Nambour.

Clive’s Headstone

References:

Aboriginal History Vol. 19, No. 1/2 (1995), pp. 141-153 “Identifying the process: the removal of ‘half-caste’ children from aboriginal mothers” by Suzanne Parry, Published By: ANU Press

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Report, Bringing them Home

Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, April 1997

Written by Gordon Plowman with memories provided by his brother David, and with some research on his early years and his years in Montville by Cate Patterson with additional memories from his daughter, Ros. March, 2022

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.