Sawdust and Steam: The story of the Flaxton sawmill, 1936 to 1963 by Gordon Plowman is a delightful account of the history of the sawmill along with entertaining anecdotes of the many folk his family encountered while living in Flaxton. This 9000 word story has been divided into 7 parts for ease of reading online.

Part 1 (The Case Mill, 1936) told how the Plowman family arrived in Flaxton in 1928 and proceeded to farm in the district and later establish a sawmill. Here author, Gordon Plowman, shares his and brother David’s memories of how the case mill expanded to become a full size hardwood mill. Read on for Part 2 (The Hardwood Mill, 1938)

Income from the case mill put food on the table but not much else so Dad decided to build a full-size hardwood mill and take advantage of the abundance of suitable logs available from the Flaxton Forest Reserve. He formed a partnership with his Mapleton mates, Jimmy Nevin and Freddy Bruhn and together they planned their new venture. They sourced as much second-hand machinery as they could and Dad commenced the installation. Nugget Evans, who ran a carrying business at Maroochydore, bought a donkey-boiler and a steam engine to the site. They planned the mill so that a belt drive from the steam engine drove a countershaft situated below the sawmill floor. Through a system of pulleys and belts, the countershaft supplied the motive power to various saws and ancillary equipment.

David recalls watching Dad build the sawmill. He remembers him boring bolt holes in huge bedding logs with an auger. These logs became the foundations for the steam engine. In remote places, sawmills and mines in particular, where steel and concrete were not readily available, logs or heavy wooden planking often served as foundations for machinery. The log foundations in Flaxton stayed in place without any problems for 14 years until an electric motor replaced the steam engine.

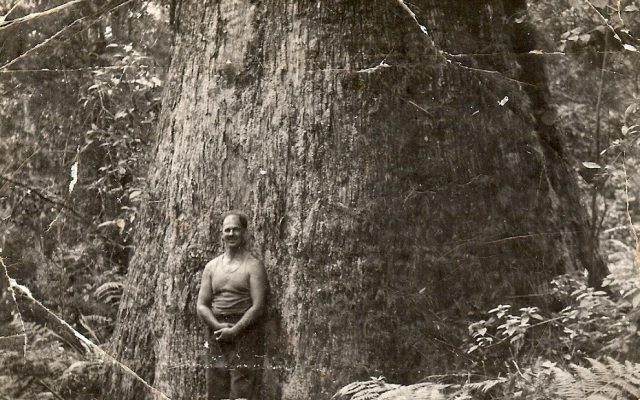

Ray Plowman beside giant blackbutt tree, Flaxton, 1947

The Flaxton sawmill, much like hundreds of small steam operated mills dotted across Queensland and New South Wales, consisted of a frame saw (breaking down saw), which cut the raw logs into manageable pieces called flitches; a number one bench to cut the flitches into sawn timber of the required sizes; a docking saw to cut the sawn timber to the correct lengths; plus a number of other essentials such as saw sharpening equipment, winches and trolleys. An old hit and miss engine pumped water from a well beside the nearby creek to feed the thirsty boiler. At a very young age I remember Dad teaching me to dog-paddle across the boiler water supply tank, completely oblivious to the two-metre depth of water below me.

Round logs, when cut into squared timber, produces quantities of waste wood which was used as a free source of fuel to fire the boiler. The working sawmill on public display at Gympie Woodworks Museum is typical of this kind of installation.

In 1936 the Flaxton sawmill stood finished and ready for operation. Dad set the fire in the boiler and the three joint owners watched nervously as the pointer on the steam pressure gauge gradually began to move up to the rated pressure. Dad held a steam engine driver’s certificate and so he supervised proceedings. He opened the steam drains to warm the engine and the steam range. Steam hissing from the drains outside the boiler house, turned into white clouds of vapour then disappeared into the atmosphere.

Now came the moment they had waited for. Dad closed the drains and swung open the main steam stop valve. All eyes turned toward the engine. With hardly a sound, the engine sprang to life. The piston rod and cross head shuttled back and forth; the crank shaft powered the flywheel up to a speed where the spokes became an invisible disc of rotational movement; the back and forth movement of the eccentric rod drove the slide valve to admit steam to the cylinder at precisely the right moment. The heavy weights on the centrifugal governor spun in a fuzzy blur of motion. All the sawmill machinery whirred into action. The saws and machinery were ready to cut the first timber. The Flaxton sawmill was in operation and the three owners set to work cutting logs into sawn timber.

In State owned forests, tight control and regulation are necessary to maintain a healthy and sustainable industry, prevent the over-utilisation of this precious resource and to cut down on waste. Businesses licenced to log these forests were required to observe these requirements and to pay royalties calculated according to the cubic capacity of the timber produced by each tree and the grade of the tree. For example, a higher royalty applied to a first-grade species such as blackbutt (Eucalyptus pilularis), and a lesser royalty for a third-grade tree such as grey gum (Eucalyptus major). The licensee could only harvest trees previously marked as suitable for logging by a forestry officer. As each marked tree was fallen, the licensee then marked the remaining tree butt with his branding hammer. The Flaxton sawmill held the brand, FX4. This procedure enabled both the Forestry Department and the sawmillers to keep their records accurate and also help to determine the value of royalties payable.

An anecdote from the 1940’s involved the forestry officer, Jimmy Golden, the man who kept tabs on all forest activities. He had occasion to check something in the Flaxton forest on a weekend. By chance, one might say by surprise, he encountered Tim Clacey walking along an old snigging track.

Tim and his wife lived in a cottage in Flaxton on the eastern side of the range. City folk today often aspire to live sustainably in the country. Tim was the epitome of that dream. His comfy cottage contained his stunning collection of butterflies and in another display case, bird’s eggs, all neatly identified museum style. He grew all his own vegetables and some fruit trees. As a farm labourer he is remembered by many as a silhouette against the setting sun with his chip-hoe slung over his shoulder, wearily trudging his homeward way. In his spare time, he liked hunting wild game. He had learned in his native England how to set snares to catch wild hares. He shot pigeons with his shot gun and if, in the course of his wanderings he came across a big snake, he would kill and skin it. Large snake skins of good quality were worth a good deal of money as were the skins of water rats, once plentiful in the swamps and streams of the Blackall Range. These creatures, like the koala, were hunted almost to extinction.

Tim knew it was illegal to shoot anything in a State Forest which is why he did his poaching on a weekend when no forestry officers were supposed to be about to catch him. Unfortunately for Tim, he did get caught. Jimmy Golden used to tell the story of their encounter: When the two men met unexpectedly, Tim had a canvas bag strung over one shoulder and his shotgun over the other. “Hello there, Tim. What’s in your bag?”

Tim replied, “I’ve got sticks in the bag, kindling for my kitchen stove.”

“Well,” said Jimmy, “this is the first time I’ve seen sticks with feathers.” The tail feathers of one of Tim’s quarry was sticking out past the top flap. In a way, this was Tim’s lucky day. Jimmy let him off with a stern warning.

Part 3, (Other timber cutters, 1936-39) continues the story of Sawdust and Steam

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.

©2016 Montville History Group. All rights reserved.